Last Tuesday a stormstorm hit Vermont. That's nothing out of the ordinary, of course. But this one had an unusual bite to it. Temperatures hovered around 25-33 F for two days, meaning snow fell with sleet. The stuff attached itself to trees, melted a little, then froze into massive, heavy weights. A second wave followed on Wednesday, piling on top of the first.

Our trees - remember Vermont is very forested - bent, then bowed, sometimes arcing down to the ground.

Some limbs and entire trees were too weak to bear the burden, and snapped clean off. For days we heard muffled CRACKs from the woods, and glimpsed boughs topple down through other trees and ground cover, slapping down into snow drifts.

Some limbs and entire trees were too weak to bear the burden, and snapped clean off. For days we heard muffled CRACKs from the woods, and glimpsed boughs topple down through other trees and ground cover, slapping down into snow drifts.Some of those arboreal missiles hit power lines.

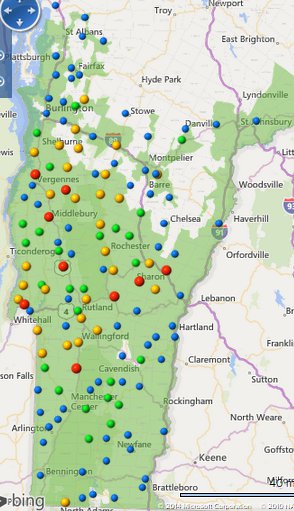

More than a few, actually. More than 100,000 Vermonters were out of power over this week. Our largest electrical utility, Green Mountain Power, fielded hundreds of repair crews drawn from many states and Canada. Frustratingly, these snow-and-ice-bound trees sometimes took down lines days after the storm. New outages appeared as old ones were fixed: one step forward, two steps back at the worst.

More than a few, actually. More than 100,000 Vermonters were out of power over this week. Our largest electrical utility, Green Mountain Power, fielded hundreds of repair crews drawn from many states and Canada. Frustratingly, these snow-and-ice-bound trees sometimes took down lines days after the storm. New outages appeared as old ones were fixed: one step forward, two steps back at the worst.

At our house this meant lockdown for a couple of days. We couldn't drive out for a day or so, as our little, class-4 road doesn't get plowed for a while. Our brave UPS batteries kept internet access and computers alive for a few hours. Once they ran dry we were back in the 19th century, with some curious dark artifacts of the future.

So we stayed at home, offline. During daylight my son, Owain, and I walked the land and the lane, checking out storm damage, looking for people to help. Indoors we read while there was light (this and that) and fried food for meals (the stovetop is gas-fueled, and ignites with a match, unlike the oven).

The landline phone worked, drawing its necessary trickle of power from the phone line itself, so we could call for help and information. It as our only contact with Gwynneth, our daughter away at university, studying disaster management, of all things.

The two wood-burning stoves kept us warm. The animals were happy to sit with us. With nightfall came the excellent, massive darkness of mountain woods, along with a strong desire to sleep. We woke with the dawn.

Eventually the roads cleared, after being repeatedly plowed, and we could drive out and along the mountain. Our town was buried under snow, and most folks were out of power. Roads were icy, snowy, and canopied with heavily-bent trees. We could also drive down to the foot of the mountain, and so commenced raiding town for electrons. Middlebury town's library hosted many like us, storm sufferers, offering electrical outlets and WiFi. My wife, son, and I camped for what seemed like days, frantically catching up with the online world. Among other things, I blogged events at our town blog. We felt like nomads, ready to up and move to wherever the precious electrons could be found.

Eventually the roads cleared, after being repeatedly plowed, and we could drive out and along the mountain. Our town was buried under snow, and most folks were out of power. Roads were icy, snowy, and canopied with heavily-bent trees. We could also drive down to the foot of the mountain, and so commenced raiding town for electrons. Middlebury town's library hosted many like us, storm sufferers, offering electrical outlets and WiFi. My wife, son, and I camped for what seemed like days, frantically catching up with the online world. Among other things, I blogged events at our town blog. We felt like nomads, ready to up and move to wherever the precious electrons could be found.After a few days of this, our home landline gave out. (We can't get cell reception anywhere in or near our town; that's a Vermont thing) We had no means of communicating with the world, save by people visiting us or, more likely, our traveling to them.

Meanwhile, utility crews worked long hours, picking up trees, repairing lines, and repairing them again.

As the storm and aftermath continued, our town opened up its fire station as a community resource. A massive generator powered the building for a few hours each day. People visited to enjoy lights, seeing neighbors, taking a hot shower, charging mobile devices, and other modern amenities, before heading back home in a kind of dark 19th century reenactment.

After several more days, our power came back.

It was an anxious, delirious moment. "I can press a button and light appears..." mused my son. We frantically used every electrical function we could: washing dishes in hot water, washing clothes, baking a pizza, firing up the Xbox, charging up phones, sucking down blessed wireless. And every minute, at first, we feared it would all go away.

Which turned out to be an accurate fear. A few hours later, after nightfall, we all heard a tremendous BANG! from outside. Immediately - less than a second - came a POP! from withing the house. Lights flickered. Another POP! and another. A tiny flame coughed out of my treadmill, followed by smoke. "I think this lamp's on fire!" yelled my son. Devices powered up, shut down, powered back up in under a second. Lights flickered faster, like strobes. POP! "I'm killing the main!" shouted my very smart wife, charging across the house to the breaker panel. POP!POP! POP! CLICK and utter darkness came right down. The sighing sounds of devices powering down drifted across shadows. I flicked on a flashlight to see smoke curling out of my treadmill.

I called the electrical utility once more.

A legion of men in trucks and hardhats arrived in the very, very dark night, shambling across our woods. It turned out that a treetop had broken off its trunk, fallen over, then speared our power line, hence the BANG! This opened up the neutral line in the power cord, freeing up the actual power lines to hurl whatever voltage they wanted, the strength varying wildly by seconds. This meant rapidly repeated power surges and shortfalls; the surges reached blow-up-your-appliance levels right away, hence the POP!s.

The crews worked into the night. My miserable son and wife, heartbroken from a taste of normal life, gradually fell asleep. I watched saws on 25-foot poles cut, headlamp flashlights stab through the woods, trucks come and go. I listened to the saws, to workers hollering at each other, boots crunching through snow. To stay awake I read (this) by the light of one flashlight. By midnight the line was fixed. I threw the main, and lovely light filled the house.

But not so brightly as before. Several lamps were dead. As was the tv, the XBox, the fridge, the hot tub motor, and my treadmill. Computers were spared, as were routers. We set insurance claims in motion.

So what did we learn from this strange, stressful weak?

- The advantages of being offline are massively overstated. For us, an involuntary internet break is a huge problem. Owain, being a teenager, uses the internet for school, for his writing projects, for entertainment, and socializing. Without them he's happy to read books, play games, talk, think, and build things, but he does those anyway. My wife and I run our business largely online, so every day offline is a blow. I did feel my life slow down, being offline, but this wasn't relaxing. It meant I was missing what I needed to do, and couldn't respond. Maybe if I plan such a "vacation" ahead of time it would be easier. I did not feel more attuned to objects and nature. This is probably because I already feel that way, thanks in part to our homesteading life.

- While this was an interstate storm and a statewide problem, the solutions were all hyperlocal. The federal government played no role. Nobody we spoke with invoked FEMA or expressed a desire for military assistance. The state government: ditto. The governor said little, and the only action I can find him taking was flying over a couple of towns, five days in. No other towns were helpful, except for several businesses and a library in Middlebury. Media attention flagged quickly, as far as I can tell, even in Vermont media. No, getting through the storm and aftermath was about my family and our tiny town. This may be a very New England thing.

- I wish we could generate our own electricity. We already have our own water supply (a well), heat entirely by wood, and raise a proportion of our food from animals and plants we raise. But electrical power is beyond us. This land is too forested for solar, unless we clearcut a huge area. The atmosphere is gentle, carrying winds too slow for wind power. There isn't a body of moving water big enough for even basic hydroelectric. Maybe we should start taking geothermal seriously.

- Stressful situations lead me to do silly things in pursuit of documentation, like climbing under a fall tree suspended halfway to the ground upon a live, bowed-out, sagging wire:

(cross-posted to BryanAlexander.org)

(cross-posted to BryanAlexander.org)

No comments:

Post a Comment